Kentridge, Berg and Lulu

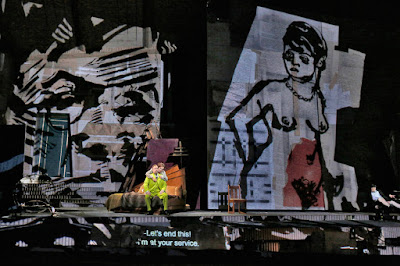

A production still of Act I from the Metropolitan Opera Premiere

Alban Berg

LULU

English National Opera, until November 19

Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, May 2017

Reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement, November 18

“Leap before you look”, runs one of William Kentridge’s mottos. It’s an invitation to look at the world from the inside, or to “peel back the layers”, to use another of the South African artist’s maxims. More importantly, perhaps, it’s an encouragement to reverse the subjugation of seeing to understanding; to loosen up the inescapable epistemological connotations the sense of sight has acquired over three or so centuries. To “see” has come automatically to mean to appraise, to size up, to control, as if Caesar’s “vidi” and “vici” have been rolled into one. But in Kentridge’s world, seeing is a less imperious business. It requires a leap of faith: only by deferring the effort to understand can we really see what is there. The world becomes brighter, louder, more dangerous.

Kentridge’s motto might well also have been Lulu’s, though perhaps “pounce before you peek” has a better ring for a woman who can sense fatal attraction in a man before he has even entered the room. And one senses that Kentridge must have known Lulu was right for him long before New York’s Metropolitan Opera commissioned him to direct their new production last year (following The Nose in 2010). English National Opera co-produced the show, and here it is conducted by Mark Wigglesworth and stars Brenda Rae in the title role, together with a superbly cast menagerie of James Morris’s Schön, Sarah Connolly’s Countess Geschwitz, Willard White’s Schigolch and Nicky Spence as Alwa.

The close fit between Kentridge and Berg relates most obviously to a shared interest in sensory overload. To listen to the score involves continually wrestling with the desires to control it and to give into it. Its symmetries and minutely coordinated textures and tonalities invite strenuous intellectual efforts that are constantly rebuffed by the music’s raw excesses, its disorientating swirls and frequent flashes of brute energy. Kentridge’s staging, with the trademark use of broad-brushed ink sketches drawn across scattered leaves of old type (see Peter Maber’s review of William Kentridge’s Thick Time, TLS, November 4) and projected across the skew-angled walls of the set, acts similarly on the eyes. The pages continually flap and shift position, or are overlaid by others. Similarly, the characters sometimes wear outsize hands and crudely sketched paper masks in a way that disrupts depth of vision. Just like the men ensnared by Lulu’s animal magnetism, we can never place what we see. Yet although the threat of disintegration is constant, the chaos is tightly controlled, the spaces organized and underpinned by the beguiling and threatening symmetry of female genitalia. V-shapes are everywhere, and they don’t stand for victory.

Berg creates a musical vacuum around Lulu by assigning specific tone rows and textures to every character – except Lulu, whose musical role, like her dramatic one, consists in acting on the others and subverting their socially conditioned desires, turning them on herself to the exclusion of all else. Appropriately, Kentridge’s Lulu is everywhere, not simply in Rae’s razor-sharp portrayal: her figure dominates the drawings on the walls, and when it doesn’t, they still seem to follow her train of thought. At the side of the stage, a constant presence throughout, is another Lulu, sitting at a grand piano in a tail coat. This is the dancer Joanna Dudley, whose interventions and strenuous sustained postures, held first from the piano stool, then the keyboard, and finally from inside the instrument, seem to represent Lulu disappearing into the music’s maw while the world disappears between her legs.

The playing and singing here are first rate. The orchestra has been superbly prepared by Wigglesworth and two assistants so that the music seems to overwhelm the stage, without drowning out the singers. Rae’s blend of vocal agility and voluptuousness mixes well with her ability to pull back on both, leaving the voice of a slightly diffident young woman, and adds a touching air to the portrayal. Morris captures perfectly Dr Schön’s failing grip on his habitual sphere of authority, while Lulu’s most devoted lovers – Alwa and Geschwitz – are very touchingly portrayed by Spence and Connolly.

A deep moral vein runs through Kentridge’s art, but its focus is intentionally diffused by an artist keen to hold off the foreclosure of judgement. Keeping Lulu’s tragic dimension in focus was therefore likely to be his biggest challenge here. For although it may be true that Berg’s opera draws its ferocious strength from depicting the feral shapelessness of Lulu’s psyche as a force for liberation and renewal of life, the drama’s tragic denouement is no mere afterthought, as some have suggested; nor is it conventionally moralistic. Rather, it is the logical result of the character’s agency in its social context. She penetrates that society at its margins and the actions and seductions through which her “earth spirit” acquires worldly character and shape are self-destructive. Indeed, it seems to be the smell of her own destruction which excites her most about her lovers. This production is unusual, though, in retaining this balance quite so well, both in Rae’s careful portrayal and in the growing and rather implacable presence of the dancer. Behind the flickering arrays of notes, images and sympathies, a blind will of steel pushes Lulu to her fate. She is murdered centre stage, behind a screen. To see it, we must leap before we look.